After so much thunders came the rain. This well-known Italian adage could well describe the attack that took place two days ago on the co-secretary of a Alternative für Deutschland, MP Tino Chrupalla. Only for one small but not insignificant element does the proverb not apply to the German situation: in Germany, by now, the storm has already started for quite a while.

That of Chrupalla, who was most likely attacked with a syringe after an election rally in Ingolstadt and is still hospitalized, is only the latest in a series of serious assaults against members of what stands as the only true sovereignist party in the Teutonic country. Last August 12, Bavarian parliamentary candidate Andreas Jurca had been brutally beaten by two unknown men in front of his home in Augsburg. On May 22, in Schleswig, in the far north of the country, Bent Lund, AfD candidate and member of Denmark's ethnic minority, had been stabbed by an iraqi national who, before carrying out the act, had apostrophized him as a Nazi. In March 2022, federal MP Karsten Hilse had been beaten at an AfD election banquet in Görlitz, Saxony, while in January 2019 it was the turn of federal MP Frank Magnitz, a former communist who switched to AfD, who was beaten into a coma after an election event in Bremen. The party co-leader herself, Alice Weidel, repeatedly threatened with death, preferred to temporarily suspend all her election appointments in Bavaria and Hesse and temporarily expatriate to Palma de Mallorca. This more than incomplete list leaves aside an infinite number of less serious assaults, vandalism, intimidation (including to family members of party members) and numerous other sabotages.

Short-sighted institutions and stagnant investigations

There is a very bad mood in Germany, very closely reminiscent of that in Italy during the years of terrorism, when killing or beating a fascist, or supposed fascist, according to the slogans of the protesters and many newspapers, was not a crime. In the face of this unprecedented wave of violence against AfD members, the authorities maintain an attitude bordering on indifference. Police investigations, when they occur, punctually stall in the face of the alleged impossibility of catching the perpetrators, who are mysteriously untraceable. This was the case, for example, in the case of Magnitz's attackers, who were never identified, and it was also the case with Karsten Hilse, whose case was dropped because the probable attacker, who was identified, turned out to be "untraceable," however. As for the Jurca attack, too, things are dragging on: only today two "suspects" were identified, when until today the Bavarian police were questioning even the assault thesis. The script, it is likely, will be repeated for the assault in Chrupalla as well: the Bavarian Police in this case, too, refuses to talk about an assault while the Minister of the Interior of the Land, the Christian-socialist Joachim Herrmann, has accused AfD of wanting to invent an assault for mere electoral calculation.

Something already seen

The blatant recalcitrant behavior, held by judges and law enforcement agencies, in conducting investigations and trials against the attackers of Alternative für Deutschland members shows that Germany is now living in a dangerous climate of violence being cleared when it is directed against AfD members and sympathizers. The scenario is, of course, reminiscent of Weimar, when those benefiting from the same benevolent disregard were the aggressors and murderers acting against centrists like Matthias Erzberger, liberals like Walther Rathenau, and communists like Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. Weimar, moreover, in its turbulent years, was characterized, just like the current era, by a long series of grand coalition governments, which often saw both the SPD and the liberal DDP, the ancestors of today's ruling party FDP, in government. Inflation, immigration, poor economic performance and war in Ukraine complete the picture.

AfD, a convenient scapegoat

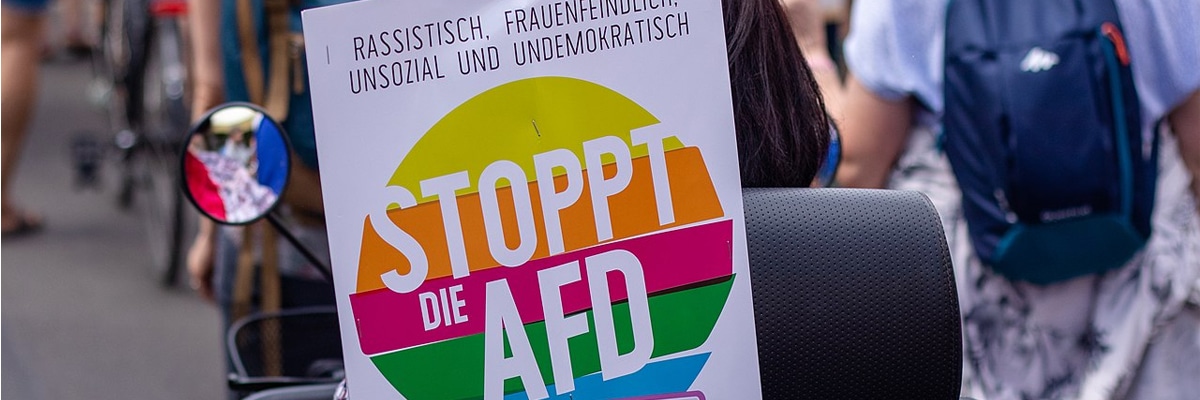

The German economy, after three decades of sustained growth, is now in recession, industry is suffering from a vicious national green deal imposed on companies (particularly automotive), while even construction is having to cancel a large number of orders given the German population's unwillingness to buy real estate in such a delicate situation. In such a precarious context, where the Scholz government is at the lowest ebb of popularity and where Alternative für Deutschland is seeing, on the wave of general dissatisfaction, its support grow in all the Länder, it becomes convenient for many in the media and in politics to divert attention to the alleged threat to the German democratic system represented by AfD, repeatedly accused of neo-Nazism, subversion, complicity with Putinist Russia, and the like. The consequences are not slow, therefore, to manifest themselves. The extremely violent German anti-fascist movement, whose actions border on, and often cross the boundaries of, terrorism, systematically proceeds to make public, online and with posters, the addresses of AfD deputies, card-carrying members and sympathizers, with the declared aim of "making their lives hell," actions that are usually followed by vandalism and assaults. That, fortunately, no death has yet escaped us, in a country where even RAF terrorists are free in Parliament to praise is, in many ways, surprising.

A wish and a duty

European conservatives, in addition to wishing that it would never come to extremes, should also begin to denounce the now intolerable situation in which AfD sympathizers and supporters live and do politics in their own country, in the same way that establishment referent parties act toward their friends in less democratic countries than in the West. Waiting is no longer possible.

Research fellow at the Machiavelli Center. A philosophy scholar, he has been working for years on the topic of the revaluation of nihilism and the great German Romantic philosophy.

Scrivi un commento