Italian politics got us accustomed to a “roller-coaster” of twirls and surprises, while its foreign policy ultimate pillars have always tended to remain the same (adherence to the North Atlantic Alliance, the Mediterranean question and the promotion of European integration), beyond the surface of spectacular albeit extemporaneous moves. Let us think for instance about the formidable “autonomy” reached during the Berlusconi cabinets and the Cavaliere’s personal friendships with Russian president Putin and colonel Gheddafi.

On the contrary, the relationships with China presented in the last decade a more complex scenario. The Chinese “pivot” decided in 2019 by then Prime Minister Conte, bringing Italy progressively within the Belt and Road Initiative, was a momentous decision, interrupting a more linear and predictable flow of Italian foreign policy, i.e. its unquestionably pro-American stance.

At the time of this shift, only Mr Guglielmo Picchi, then Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, emerged as a critical voice of caution, expressing “reservations about the strategic and economic implications of Italy's involvement in the BRI. His concerns revolved around issues such as the transparency of the agreements, the potential for China to gain disproportionate influence in Italy's critical infrastructure, and the broader geopolitical implications for Italy's alignments within the European and transatlantic contexts”[1].

While Picchi’s positions did not immediately have a defining effect in preventing the deepening of the Chinese-Italian convergence, they effectively nurtured the conservative political and military foreign policy thinking behind last December exit of Rome from the BRI, possibly with the aim to restore a “more cautious and measured approach, ensuring that certain safeguards and limits were in place”[2].

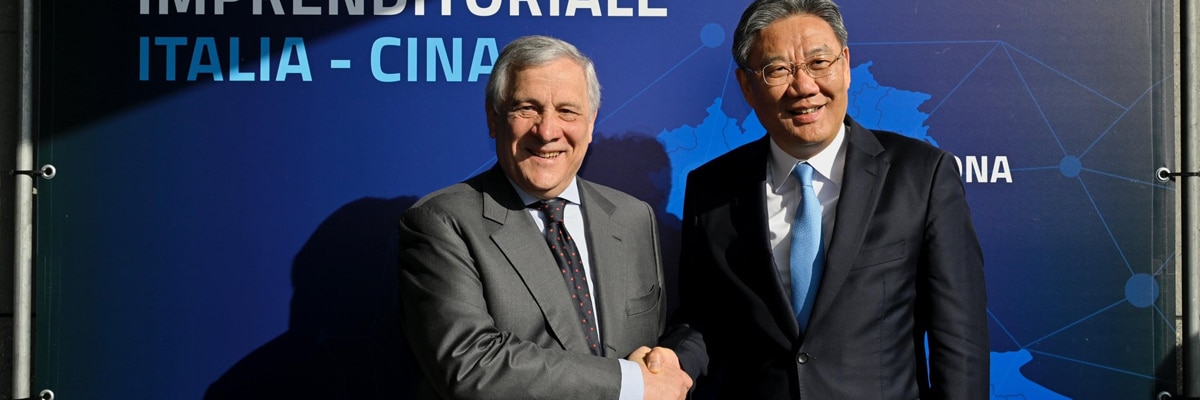

Yet, just a few months from this important shift, on 10-11 April, the Italian press rightly stressed the political importance behind the meeting in Venice and Verona between Italian Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Antonio Tajani, and the Chinese Minister of Trade, Wang Wentao. The top government officers co-chaired the 15th session of the Joint intergovernmental Economic Commission, on the margins of which, the Deputy Prime Minister of Italy seemed to give a “second life” to the “strategic trade and economic friendship” (as mentioned by Tajani himself) with Beijing.

In fact, the top Italian foreign policy decision maker declared that Italy wishes to “inaugurate a new phase of bilateral relations and invest in partnership, in the year in which we celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Partnership Global Strategic Agreement established between the two countries in 2004 and the 700th anniversary of the passing of Marco Polo”.

The Chinese rational aimes at preventing the structural and wide-ranging bilateral tensions with the U.S. to affect the constructive and mutually beneficial relationships with European partners, in order to shift them from the uncanny position of being caught in the middle of this “crossfire”.[3].

Moreover, the potential rapprochement serves the Italian need for increased Chinese direct investments and a (difficult) rebalancing of its trade balance, while at the same time expressing its hope for a more collaborating and constructive position of Beijing vis-à-vis the EU/NATO agenda regarding the Ukraine war[4].

Final comment

We are witnessing in foreign affairs to a “return of History”, to the reemergence of the balance of power, now so nicely described by Russian spin doctors as “mnogopoliarnost’”, i.e., a multi-polar world. In the context of such tectonic shifts in the moral and operational framework regulating intergovernmental relations, the new “deep forces” (as Renauvin would say) stand on the side of consolidating actors like China (or India).

The definitive crumble of unipolar means of enforcing the international order (briefly existed, recently, only at the begging of the 1990s, let us recall the fall of the Soviet Union, the consequences of Iraq’s aggression to Kuwait or NATO’s actions in the former Yugoslavia) gives way, inexorably, the regional spheres of influence and big-power politics in foreign affairs among a “concert” of major nations.

The case of China is instructive and hints to predictable consequences for its ambitions to restores what it deems to be its historic and moral right to reunite its people within one country. The consolidation of economic and trade relations with Europe, its mediation and collaboration with the Kremlin vis-à-vis the Ukrainian war, all serve as diplomatic pillars for a wider space for maneuver in fulfilling the aforesaid historic ambitions.

On the side of Italy, as a chiefly regional power, the long-term foreign policy goals are driven in part by its structural macroeconomic problems (for instance low rates of economic growth, low productivity growth, structural market rigidities), that necessitate a robust promotion of FDI and Italian export, which can be facilitated by adopting, as much as possible, nuanced, pragmatic positions vis-à-vis certain international issues.

As a result of these structural, historical considerations, has come the time for a more audacious, autonomous Italian foreign policy towards China? Has come the time for a new post-Picchi consensus? Or is the Venice meeting just another photo-op?

Note

[1] Guglielmo Picchi, “Italy’s Exit from the Belt and Road Initiative: An Analysis of Strategic Realignment and the Minor Role of Guglielmo Picchi", December 6th, 2023, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/italys-exit-from-belt-road-initiative-analysis-strategic-picchi-kckof

[2] Ibidem.

[3] Gabriele Carrer, “La Cina spinge l’Ue (e l’Italia) verso la terza via con gli Usa”, Formiche.net, April 9th, 2024, https://formiche.net/2024/04/cina-europa-global-times/#content

[4] Gabriele Carrer, “Italia-Cina, Tajani indica la via per le relazioni post Via della Seta”, Formiche.net, April 11th, 2024, https://formiche.net/2024/04/italia-cina-tajani-wang/#content

Esperto di relazioni internazionali.

Ottima analisi, complimenti.