Demography of Italy: from Unification to Fascism

Italy's resident population on January 1, 1862 amounted to 26,328,000. The newly formed Kingdom of Italy was mainly rural: 67.8 percent of Italians resided in towns with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants. The population recorded a very low average age, suffice it to say that in the decade 1861-1870 more than a third of Italians were under 15 years old. Mortality in the first year of life constituted just under half of total deaths; four out of ten children did not reach their fifth year of life.

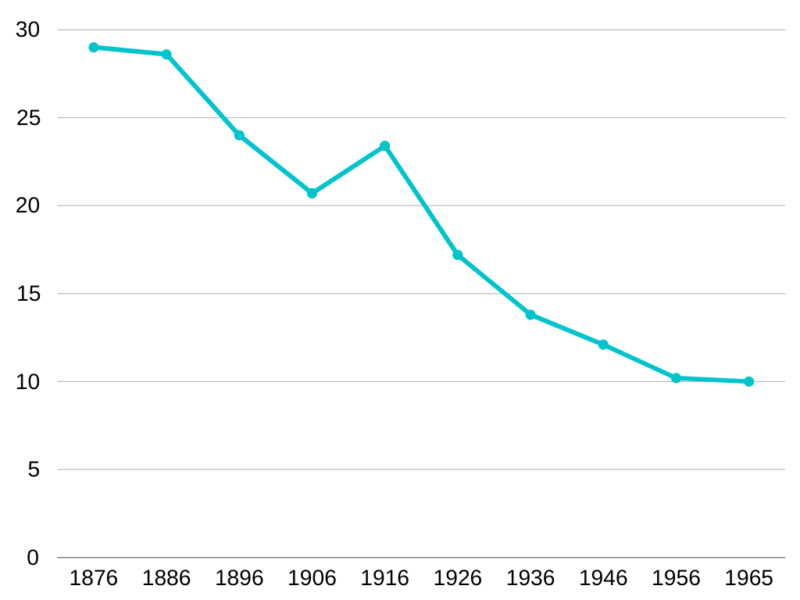

The decline in the mortality rate (ratio as a percentage of deaths to the living population, calculated on an annual basis) recorded in the years of demographic transition.

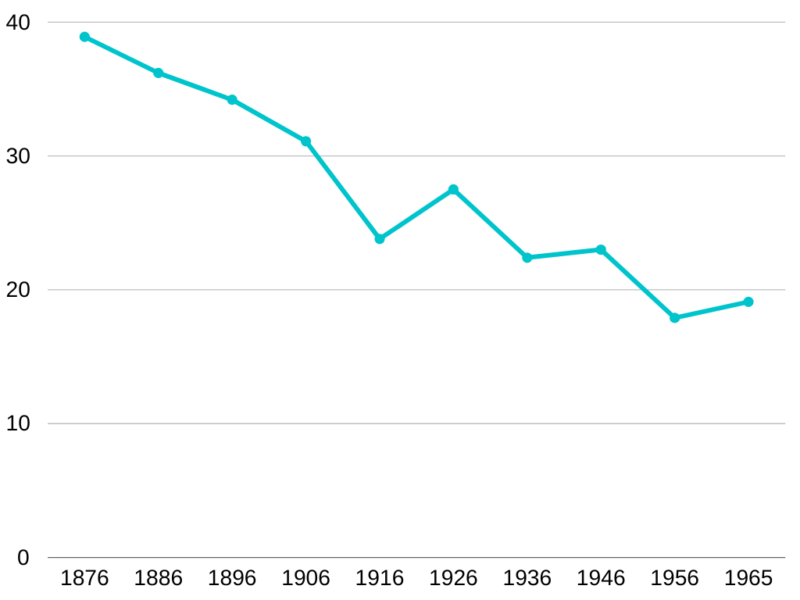

In 1876 began the demographic transition, that process in which a lowering of mortality and birth rate occurs. This process can be divided into two stages: the “health transition” (lowering the risks of death, first in childhood and then in adulthood) and the “reproductive transition” (lowering the couple's prolificacy). In Italy, the demographic transition ended in 1965. Beginning in 1880, mortality began to decline steadily. Birth rate also followed the same path, albeit more slowly.

The birth rate (ratio as a percentage of the number of births to the living population, calculated on an annual basis) recorded in the years of demographic transition

Since the last two decades of the nineteenth century, emigration has offset the increase in natural growth rates (the annual number of live births exceeds the annual number of deaths), the years 1912-1913 saw a net negative (emigrants outnumbered immigrants) of more than 750,000 Italians (2 percent of the population). During World War I the birth rate declined, while the death rate increased, partly due to the Spanish flu. Immediately after the war birth and mortality rates returned to pre-war levels, and then resumed their gradual decline.

| Year | Population | Live births | Deaths | Natural balance |

| 1915 | 37.997.000 | 1.138.000 | 848.000 | +290.000 |

| 1916 | 38.166.000 | 906.000 | 894.000 | +12.000 |

| 1917 | 38.118.000 | 735.000 | 990.000 | -255.000 |

| 1918 | 37.844.000 | 676.000 | 1.324.000 | -648.000 |

Fascism: “denatality is the most urgent among the problems of the age”

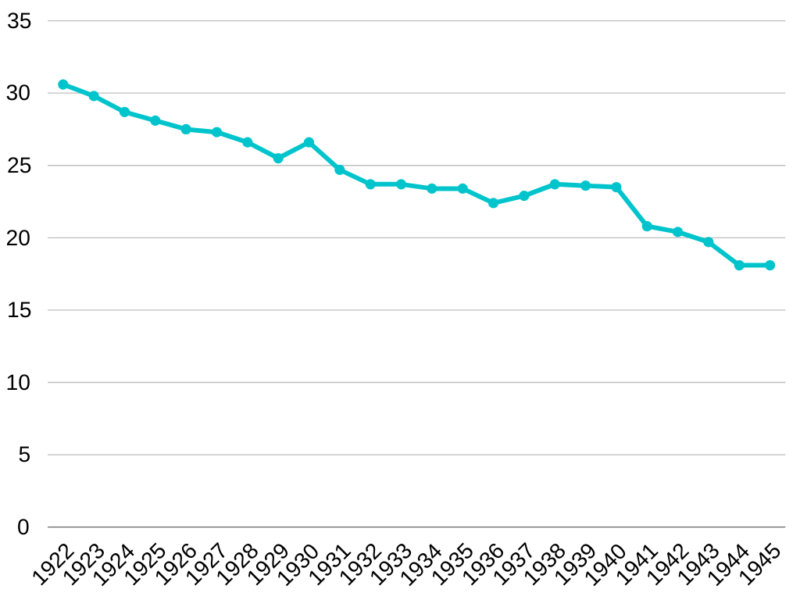

In Europe between the two world wars, denatality began to worry demographers and governments. In 1928, German statistician Richard Korherr published a text with the apocalyptic title: "Geburtenrückgang – Mahnruf an das deutsche Volk". The increasing denatality of European peoples would lead, in the long run, to the aging and disappearance of Europe's native peoples. The preface to the Italian edition of Korherr's text, was written by none other than the then head of the Italian government Benito Mussolini. In his lengthy introduction - echoing the author's theses - Mussolini asserted that the declining birth rate is the direct consequence of urbanism. In fact, already in the 1920s, in some large cities in central and northern Italy, there was a negative natural balance (deaths exceeded births) offset by the fertility of the rural population.

Richard Korherr after Hitler seized power joined the National Socialist regime and actively collaborated with the racist policies promoted by the SS. Although after World War II he was allowed back into university teaching and public office, his collaboration with the Nazis threw discredit on his studies, even pre-dating the regime.

In any case, his theses on urbanism and denatality were soundly based, shared by many scholars, philosophers and politicians of the time.

For this reason, the Fascist government tried to “keep” the population in the countryside: few children were being born in the big cities. However, according to "Storia demografica dell'Italia dall'Unità a oggi", (Istat, Feb. 7, 2023):

"In the 1930s urbanization continued, despite measures to limit access to residence and work in the cities and encourage internal colonization (in particular, Laws 358/1931 and 1092/1939). Between 1931 and 1936 the population share in municipalities with up to 10,000 inhabitants declined by 1.6 percentage points, to 49.6 percent [compared to 51.2 percent in 1931], while residents in those with over 250,000 inhabitants grew by half a million (to 15.8 percent). By 1936 Rome and Milan had exceeded one million residents, Naples had 850,000 and Genoa and Turin over 600,000."

Birth rate, 1922-1945

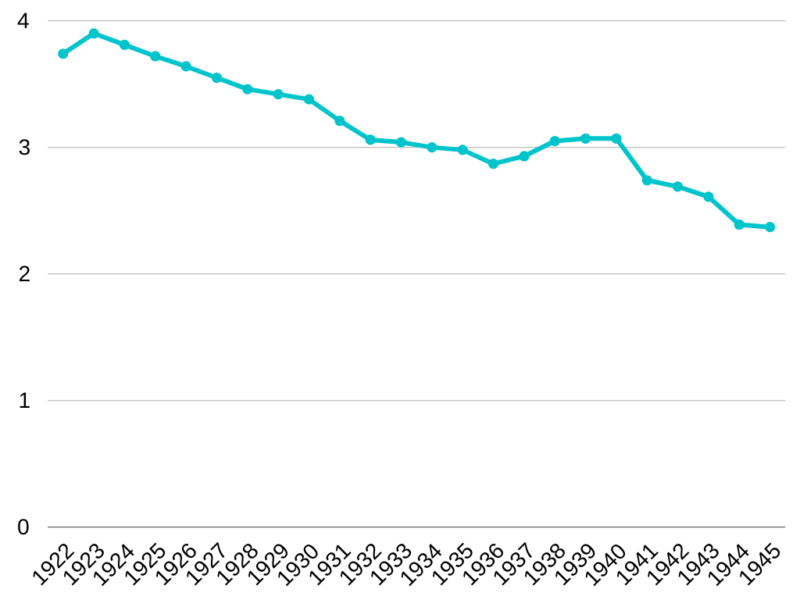

During the 20-year Fascist period, the birth rate continued to progressively decline.

Mussolini wrote in the preface to Korherr's book: “The city dies, the nation -without the life-bloods of the youth of the new generations anymore - can no longer resist - composed as it is now of vile and aged people - a younger people screaming at the abandoned frontiers. This has happened. That can still happen." Mussolini sees in the pressure of younger peoples a threat not only to Italy, but to the entire West, which is in danger of “being swamped” by peoples of color who-supported by a fecundity unknown to white peoples-would inevitably, sooner or later, “knock” at our borders.

In 1935 another book was published with an equally apocalyptic title, mitigated - only in part - by the question mark: "Europa senza Europei?" by Guglielmo Danzi. The author takes up Korherr's theses, arguing that the cause of the denatality is to be found in urbanism and attached “law of comfort.”

"The descendants of the conquerors of other ages have become veritable bilges of philistinism and bourgeois softening. Children? They cost money. That's one of their sayings. The law of comfort does not allow them to manufacture brats: on the contrary, it provides the most modern anti-fertilizing istruments at very convenient prices."

The argument at the time was this. Basically, welfare (“comfort”) induces people not to reproduce in order not to have to give up-not even a fraction-of said welfare. No responsibility. Only material enjoyment. Danzi analyzes the - already at the time - worrying European demographic situation by concluding:

"Will the children of children see the skies made dark by hundreds of thousands of aircraft bearing to the places of old peoples new migrations of young peoples? Will rivers of human flesh overflow from distant riverbeds, turning to the twilight West? Will Europe sink into the night? Will strange men come to colonize the lands fattened by so much death?".

By the 1920s and 1930s, ethnic replacement was already being foretold. No conspiracy. Just numbers.

Third and last text of note, published in 1936, is "La politica sociale del Fascismo" published by the Fascist Party. The Fascist State emphasized the importance of the birth rate, not only because depressed demographics do not permit a “power policy,” but because of the simple fact-if one can call it that-that a compression of the birth rate, in the long run, leads to the death of peoples. The text specifies that “if the decrease in mortality partly compensates for the phenomenon of the decreasing birth rate and still allows for some countries a slight natural increase in population, nevertheless it is to be considered that this situation is transitory and due only to the current favorable age composition of the population.”

In fact, almost 60 years after the publication of this paper, in 1993, Italy recorded a negative natural balance for the first time: the number of deaths exceeded the number of live births. Over the course of the twentieth century, the population increased because there was a lowering of mortality and an increase in life expectancy: people are living longer, in absolute terms live births-except for a few years-have gradually decreased. Suffice it to say that during the two world wars Italian women gave birth to twice as many children as today.

| Year | Live births | Deaths | Natural balance |

| 1915 | 1.138.000 | 848.000 | +290.000 |

| 1916 | 906.000 | 894.000 | +12.000 |

| 1917 | 735.000 | 990.000 | -255.000 |

| 1918 | 676.000 | 1.324.000 | -648.000 |

| 1940 | 1.040.000 | 616.000 | +424.000 |

| 1941 | 930.000 | 659.000 | +271.000 |

| 1942 | 919.000 | 704.000 | +215.000 |

| 1943 | 890.000 | 792.000 | +98.000 |

| 1944 | 822.000 | 732.000 | +90.000 |

| 1945 | 821.000 | 645.000 | +176.000 |

| 2020 | 404.892 (di cui 59.792 stranieri) | 740.317 | -335.425 |

| 2021 | 400.249 (di cui 56.926 stranieri) | 701.346 | -301.097 |

| 2022 | 393.33 (di cui 53.079 stranieri) | 715.077 | -321.744 |

Despite the family-supporting policies promoted by Fascism, the fertility rate of Italian women continued to steadily decline. The average number of children per woman fell from 3.74 in 1922 to 2.37 in 1945.

Average number of children per woman, 1922-1945.

[2 - continues - Part 1 can be accessed by clicking this link]

Sources:

Popolazione residente per sesso, nati vivi, morti, saldo naturale, saldo migratorio, saldo totale e tassi di natalità, mortalità, di crescita naturale e migratorio totale – Anni 1862-2014 ai confini attuali, seriestoriche.istat.it

Storia demografica dell’Italia dall’Unità a oggi, Istat, 7 febbraio 2023

De Rose-Rosina, Introduzione alla demografica. Analisi e interpretazione delle dinamiche di popolazione, EGEA, Milano, 2022.

J.-C. Chesnais, La transition démographique, Paris, Puf, 1986, pp. 294-301.

Danzi-Korherr, Europa senza europei?- Regresso delle nascite: morte dei popoli, Editrice Thule Italia, Roma, 2022

Partito Nazionale Fascista, La politica sociale del fascismo, testi per i corsi di preparazione politica, La libreria dello Stato, anno XIV E. F.

A maverick of nonconformist thought, he writes for several newspapers and blogs. He is interested in demographic dynamics, history, geopolitics and "fashionable ideologies."

Scrivi un commento